- Home

- Louis Guilloux

Blood Dark Page 2

Blood Dark Read online

Page 2

Like Le Sang noir, Blood Dark came from a conversation with a friend—Breton poet and playwright Paol Keineg. I liked both its weirdness and the way it makes “dark” less adjectival and more symbolic, representing both the middle of the war and the ignorance of the town’s inhabitants who are blind when it comes to the consequences of their patriotism. Last, for a novel with a wine-soaked protagonist who embarks on many asides and long journeys through the labyrinthine town of Saint-Brieuc, I liked the echo of wine-dark. This title hints at an Odyssean allusion that is not in the original. But it is consistent with Guilloux’s ambitions, which are more modern than they first appear. It would be like him to subvert the old myth of homecoming while placing his masterpiece among the classics—a context this book deserves.

—LAURA MARRIS

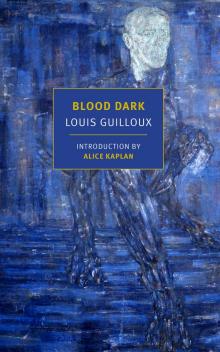

BLOOD DARK

To Renée

MAÏA ENTERED with a racket of clogs. Not the slightest care for the sleeper stretched out, fully clothed on the couch, his little dogs around him—she knew that he wasn’t asleep.

What did she come in here for? Stopping in the middle of the room, she reached to open the shutters, then hesitated.

On a little side table, near an open book and a pile of grading scribbled with red ink: her workbasket. She bent down, rummaging. What was she missing? A needle? A spool of blue thread?

She didn’t know how to read, but it still bothered him to think she could see his papers. Pimply dunces! They’d found yet another way to mock him. One of them had traced across the page, in big letters: CRIPURE! My name is Merlin! Hadn’t he shouted My name is Merlin! countless times, banging his fist on the lectern? Yes. And so what? It had only made them snicker. If anything, they’d become even more determined to call him Creep . . . Creep . . . Cripure behind his back, to write his nickname on the blackboard. Filthy rabble. And it had gone on for so many years—

Maïa was still rummaging.

It was taking a while.

He didn’t want her right then, of course. But even so his hand clutched at the slut’s hip, slipped down, reached the threshold of the skirt, disappeared. He chased off the little dogs, pulled Maïa closer. The workbasket tipped, buttons rolling. Maïa put down the newspaper—which she folded into a policeman’s hat and wore for doing the housework—and climbed onto the couch without a word.

He threw himself at her as though scaling a high wall, with a hoarse but affected shout, his eyes still closed, thinking, Why? Why? Why?

Mireille, the pretty spaniel, tugged on a panel of upholstery, growling. Turlupin, with plaintive howls, bounced around the room. Petit-Crû yapped, in his shrill, panicked voice; fat Judas wandered, a blind black ball.

“That do it?” said Maïa.

He sat up. She slid to the floor. Cripure kneeled on the couch, thighs naked, fists pressed into a cushion, and began to insult her, scarlet-faced. He couldn’t stop himself.

“You’ve tumbled in every haystack in the country . . .”

Why bring it up? Case closed, finished. That had only lasted for a little while anyway—she’d gotten married, been widowed. Since then she had only been with him and Basquin. But Basquin—she’d met him first. And so what, hadn’t he told her a hundred times that it was precisely because she’d done it for money—not worth busting your skull to figure that out!

“Want some more, kitty cat?”

“You’re disgusting.”

She didn’t insist.

It was strange that he hadn’t yet told her to go find forty sous in his waistcoat pocket, since that was usually his first insult—her price, forty sous—

She helped him readjust his clothes. Passive as a child, he let her do it.

“Filth—”

She didn’t flinch.

Hadn’t she heard all about that night, at the brothel, when he insulted a girl who was coming back from her room, client in tow? He’d rushed at her. He wanted her right then and there. It excited him, he said, to think she’d just done it. They had a hell of a time calming him down, but in the end, he hadn’t wanted the girl anymore, and he’d left. There are men like that, thought Maïa. It meant little to her that in leaving the brothel, Cripure had muttered strange threats about the officers, leading those who witnessed the scene to think he was drunk or maybe crazy.

He finally quieted, stretched out. Maïa picked up her hat, righted the workbasket. One by one, the little beasts jumped on the couch and settled around him again. He reached out a hand to pet them.

Maïa returned to her housework. Cripure could hear her coming and going, pushing the broom, clomping in front of the sink. Upstairs, Amédée was getting dressed. He kept walking back and forth across the attic where they had made him a bedroom. The loud steps right over his head exasperated Cripure.

He consoled himself that this was the last day. Tomorrow this penance would be over. But right away he was guilty of an inhuman thought: Wasn’t it actually today that Amédée was returning to the front? If he had coped for five long days, he could certainly put up with him for another few hours . . .

Of course, in that house (which, with a bourgeois affectation, he called “rustic,” though in this case, the word was apt) it was pretty hard to put a guest anywhere but the attic. This little house, which Maïa had inherited when her husband died, consisted of only two rooms—the “study” where Cripure was sprawled at that moment and, beside it, the kitchen, which also served as a bedroom. And above, the attic (half storage, half garret) where Amédée continued to make so much noise with his foot soldier’s boots. But he would go out soon, probably to meet up with some barmaid.

Thank God Cripure could go late to school this morning. An hour of class—ethics, for third years (those urchins!). And then this afternoon, that party . . . What a bore.

He sighed, opened his eyes, confirmed with pleasure that the shutters were closed. Somewhere in the neighborhood a military unit was training, endlessly repeating the same formation. Fine! Fine! All that was their business. Love for one and all! They needed a God to come and teach them to love, but they learned to hate all by them-selves . . . Fine!

Cripure sat himself back down on his couch and the little beasts stirred, wagging their tails, but as he stopped moving and closed his eyes, they became still again.

Not much would change the day he stretched out, just like this, in his coffin. What difference would it make? Nothing missing but the little voice in his head, so vain, so obsessive, that he pompously called his thoughts, nothing missing but the coward’s angst that clutched his heart—

He had undoubtedly drunk and eaten a little more than was sensible on the way home from his cottage last night. He had gone straight to bed, but sleep had been slow in coming. Recently, the nights he’d once loved for their silence and their peace had nothing to offer him except lingering anxiety. When he couldn’t sleep, he was afraid. The slightest creak of a floorboard—he would jump out of bed, his heart pounding. Maïa lay next to him sleeping, alas dreamless, leaden.

Last night, he had barely closed his eyes, hearing, until late, the chorus of Russian soldiers billeted close by.[1] Then, as so often happened, he heard the Clopper.[2]

At night, the Clopper, who hid by day—nobody knew what he did with his time—would make the incredible effort to don his frock coat, to climb down his stairs or rise out of his cave. He would appear in the streets, sidling along the edges of the walls like a marauder. Clop! Clop! Clop! The Clopper announced himself, dragging his paw, and with every step the iron tip of his cane slammed the stones of the sidewalk, echoing like a cracked bell. He paused, sometimes for a while, leaning on his cane, chin in hand, for such a long time that Cripure thought he was gone. But—clop! clop! clop! And once again the night resounded with the solemn beat of his steps.

Why did he come back so often? Why to my street? That night, Cripure had gotten up cautiously, had opened the window a crack: gaslights in the silence. It wasn’t easy to spot that silhouette in the shadows, and it was even harder to stop searching for it. He’d waited

a long time to see that morsel of night sliding along the walls—he’d sometimes watched until dawn. Clop! Clop! Clop! Still nothing but steps, nothing but a ubiquitous presence ready to spring from the walls. The iron tip of the cane had rung out against the stones, triumphal, like the halberds of Swiss Guards on holy days. Then nothing.

Cripure had stuck his head out: standing under the lamp, the Clopper was still as a saint in his niche. Around his bowler hat, the gaslight blazed like a stained-glass halo. Chin in the palm of his left hand, the other hand resting on his cane—what a perfect target. The day—the night—would come when Cripure would fire his revolver and—tac! tac! would settle his score. It would make so little noise, maybe just a little clicking of the hammer or the trigger. It would be more like crunching a flea under his fingernail. Just like that, the earth would be cleansed of the Clopper forever.

After the Clopper left, Cripure had gone back to bed, then slept—how?—but his sleep was laced with nightmares. Then came a furtive presence—a woman murmured in his ear: What is there to cry about? Who? Who was she? An instant after waking, he’d understood that his nocturnal visitor was Toinette, whose arrival he continued to hope for, even in the abyss of dreams, as he had hoped these twenty years. Toinette whom he had never heard from again, what had become of her, out there? Maybe she was a female clopper, like the woman who had wandered the streets of the town for years, humming airs from operettas, a horrible hunchback always leading a little dog, yellow and haggard, on a leash.

He had been tempted to pick up the book at his bedside, but thought better of it—the Memoirs of Benvenuto Cellini, no less!

He stretched out a hand to stroke the head of one of the little dogs, Mireille, his favorite.

Sweet little creatures!

But it wasn’t wise to trust them too much, either, even the little dogs. They could also betray! Stories for kids often had those faithful dogs who followed the fortunes of their masters to the point of starvation. Yes. But he had read in the police log about a man who killed himself and was immediately gobbled up by his faithful companion.

The attic door slammed and Amédée’s huge treads battered the staircase, heavy, like those of a man who finishes getting dressed while walking, buttoning his belt or his jacket. What farm-boy steps! The whole house shook.

His son went into the kitchen; Cripure peeked through the glass door. Amédée was joyfully giving orders to Maïa, who got to work serving his breakfast. Good. No danger Amédée would come to greet him. That would be after, on his way out. Amédée would open the door a crack after knocking softly. “I’m going out . . . see you later . . .” They would shake hands without looking at each other.

Cripure closed his eyes, feigning sleep. He was sure that no one would disturb him. Maïa would send any visitors away. But who would visit him? In the kitchen, Amédée was chatting with Maïa while he ate breakfast. He heard their laughter and the fanfare of Maïa’s wooden clogs on the cement. Here, no one. He murmured, “No one!”

Surprised, irritated by his own voice, he raised his eyelids. And as though he had sought a desired, maybe dreaded presence, he cast a long uneasy glance over the room.

“No one . . .”

Unless some half-crazy person appeared, like the other day . . .

He’d been nice, that young lieutenant, but naive. Ultimately, that would do him in. If he wanted to believe that humanity could be . . . bettered, well, that was his business. He’d get his comeuppance, one of these days, and break his neck. Poor kid! A waste! He was gifted, of course. His best student back then. What’s more, he had a noble character. A born victim. But this victim was no lamb to the slaughter. The lieutenant had revolted; that deserved some admiration, no matter what else you might think. Cripure could understand why officials and the elderly might be conventional—but the young! The more he thought about it, the more it seemed that one young person in a thousand was incredibly blind, and the rest were consciously abetting. This one had spoken of sweeping it all away. Sweeping! Well sure . . . Cripure would love to see that. If it were only about cleansing the earth of the whole mess of swindlers and imbeciles, to empty the world of its riffraff, he would lend a helping hand. But if they would only stop coming to him, like that lieutenant, to talk about man’s triumphs over himself. Humphgarumph as Father Ubu says, that’s too ridiculous! Outrageous lies. My argument is negative. I destroy all idols, and I have no God to put over the altar. It takes a pretty substandard experience of life to believe in such nonsense. Humanitarian paradise, sociological Edens, humpf! Just wait till he’s forty and his beloved wife has cheated on him. Then we’ll talk. Tsk, tsk. In this world, it was every man for himself, to save his own skin. And triumphs? Those of one’s own making. Yes: to be the wolf.[3]

He stayed motionless, applied himself to performing sleep. But that mouth, tightened as though in anger, the chest which rose in spite of itself, the hands upturned on the goatskin like those of a corpse—this was less the posture of a sleeper than of a conscious man suffocated by sorrow. It had returned all of a sudden, as always, like an incurable disease you’re tired of monitoring, which comes back to seize you when, almost at the peak of happiness, you hoped the truce would stretch out a while longer. So it would always go! He had counted on wisdom to come with age, like a benefit or recompense, like the spiritual equivalent of the pension that the state, in the name of retirement, would furnish him for good and steadfast service. Would the sorrow that had desolated his life never take a day’s rest? Would there be time, before death, for him to take a clear look at himself and the world? This hope, once realized, would enable him to accept a death that otherwise would be no more than a theft, a shameful fraud. But the older he got, the more he told himself that he would have to renounce this hope as well, since sorrow would not relent and since, in this moment, he was gritting his teeth against the pain, which, despite all these years, was as strong as the day after the catastrophe.

It was Toinette he had loved—he could say loved!—But he’d gotten this son of his, this Amédée, from a horrible rag of a woman, a hotel slattern who wouldn’t have been worth shaking a stick at. It happened in the same year as the catastrophe, a few months after the break with Toinette, in Paris where, under the pretext of finishing his thesis on Turnier, he had taken refuge. A memorable year in every way. He had partied endlessly: drinking like a fish, spending without counting, keeping women, losing a large part of his savings at poker, and crying under the covers in sorrow and rage when he was alone at night and thinking of Toinette. And it had to be precisely that year, when he’d had his fill of so many lovely women (by paying them of course), that he’d gotten that faded little blond pregnant.

She had come in and out of his room, dusting the furniture, re-making the bed, not speaking, just barely smiling. No one knew where she came from, if she had a life, and he had been absolutely fine with knowing nothing: a slattern. Why did that day have to be so hot, why did she come to clean the room barely clothed, a thin shirt over her camisole? And the shirt itself half unbuttoned. She did it on purpose, the slut. In any case, she hadn’t resisted. She let herself be quietly taken and pushed away.

After that, he would fuck her and reject her on a whim, a cruel game in which he was, for once, doing business with a weaker party. But he had always treated her kindly, even the day she had come to announce that she was pregnant. He had given her some money, to at least get herself a decent place to sleep, and later, he had acknowledged the child. Amédée bore his last name.

She hadn’t asked for anything. Afterwards, as before, she was always unresisting and resigned to her fate, as if nothing that happened to her, not even motherhood, could rip her from a languid dream. And spontaneously, just as he was leaving Paris, he had promised to send her a monthly check.

He had kept it up for the first four years, not otherwise caring for news of his son. But towards the end of that period, he got it in his head that maybe the boy wasn’t his, that he’d been fooled again, taken like an

imbecile, and that this slattern he thought was so stupid had at least had the sense to choose, from the mob of her lovers, the most idiotic—meaning him. Me! Having acquired the “moral conviction” that during the last four years he’d been the victim of a swindle (a point of view that also satisfied his greed), he’d stopped sending money. No complaints. The slattern didn’t even seem to perceive that the money had stopped, though she could have easily made a fuss since he had already committed the unpardonable idiocy of legitimizing this child with thirty-six fathers. With that in mind, a long silence stretched. But not forgetting.

Once the war broke out, Cripure had calculated that the slattern’s child must be old enough to get himself killed. And he had wanted to find him.

Letters sent to the old addresses had come back to him. He wrote to the mayor of the little village where the child had grown up: Amédée had already been deployed to the front for a year. A correspondence started, and it was arranged that Amédée would come see his father during his next leave. They would say he was a nephew.

Maïa had agreed.

What a ridiculous scene at his arrival! That anxious sob which had gripped his throat at the sight of the young man, and that extravagant way he’d opened his arms, shouting, “Embrace me, I am your father!” Would the parting scene be equally grotesque? He feared so, all the more because Amédée’s stay with him, all things considered, had been a mistake, a bitter pill. He didn’t feel so much responsibility for Amédée and the slattern. This situation was probably due in some part to indifference, and because he had not let himself forget that Amédée might not be his son.

Blood Dark

Blood Dark